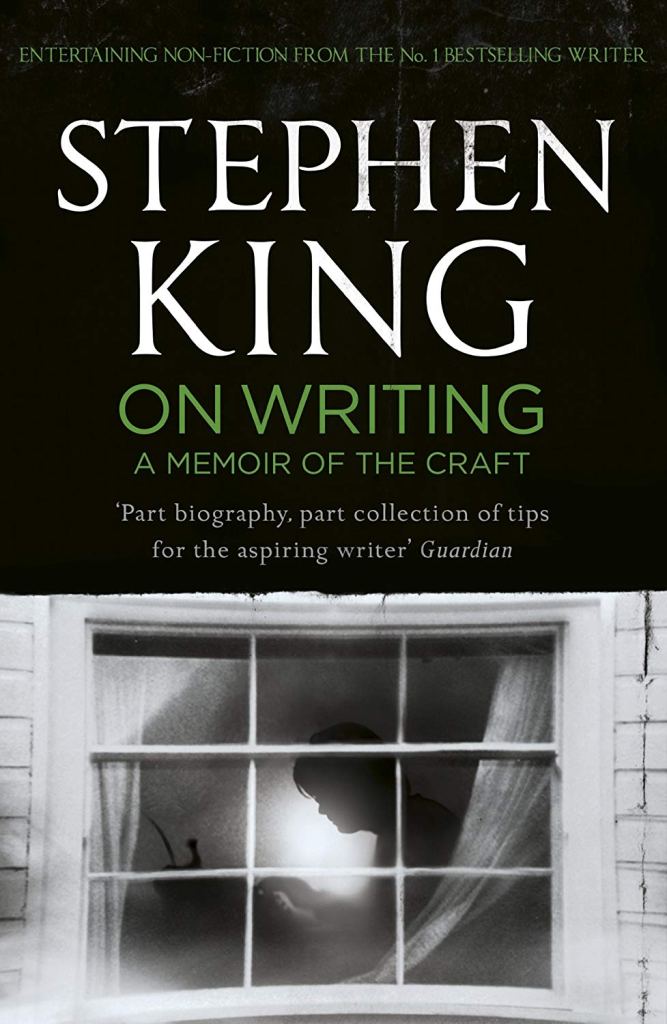

I’ve never been an avid reader of Stephen King’s novels, but his name and many titles speak volumes about his credentials as a writer. Part memoir, part how-to guide, On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft sees him provide many lessons in a straight-forward and down-to-earth way, and is a must read for anyone aspiring to the craft.

Naturally, while reading it, I felt the need to take a few notes.

His first section is autobiographical, telling of his upbringing and early writing pursuits. He certainly didn’t have the easiest childhood. He and his brother were children of a single parent in a struggling household. Even from a young age though, he showed a love for crafting stories, which evolved into work he did for his brother’s small newspaper.

I related to one of King’s first serious writing jobs; sports reporting, given some of my first published work was also sports related. Let’s hope that he and I may yet share other parallels.

King admits he didn’t much like his first book Carrie. It’s disturbing to think that, had his wife Tabitha not fished those first few pages out of the trash and insisted he finish it, the world might not have ever known his name.

I imagine that he wouldn’t have continued seeing success over the years were it not for his consistency and discipline. These clearly played a role in his later career where he eventually overcame a dark period battling with drug and alcohol abuse. Much of these two strengths boil down to his mastery of writing’s essentials.

The book’s second half is where switches to detailing the practical aspects of writing.

It’s here the book’s educational tone shifts up a gear. The writer’s ‘Toolbox’, as he calls it, I found particularly encouraging. He states that the basics of writing ultimately boil down to “vocabulary, grammar and elements of style”. It’s that simple, huh? I think, suddenly feeling a boost in confidence.

King makes many of the same comments that people have often made about my own writing. Write economically. Make every scene service either your plot or characters. Make sure your backstory’s worked out. Hearing the same advice from multiple sources really nails home its importance. Putting it into practice though is harder. For example, I still struggle to make my writing less cluttered and wordy, but King’s words on style help to sharpen this. What’s useful about his advice is his way of pointing out dos and don’ts; handy for someone like me who learns by example.

For King, vocabulary doesn’t just consist of having a sizable word pool, but also knowing how to use it. What’s harmful, he says, is “looking for long words because you’re maybe a little bit ashamed of your short ones. This is like dressing up a house pet in evening clothes.” – embarrassing for both you and your pet. His main point on grammar is to ensure sentences always consists of a noun and a verb. As for style, he insists on leaning heavily toward using active verbs, this being where the subject is doing the action rather than vice versa (passive). “The writer threw the rope” is way more succinct than “The rope was thrown by the writer”. His other main point is to avoid adverbs where possible. Using stronger verbs makes things a lot more stream-lined, but still keep vocabulary in mind. Don’t get too fancy with your words. You want your writing to be crisp.

King makes an interesting statement here about paragraph length as an element of style. The shorter the paragraphs in a book, the easier a read it’s likely to be. Heavy-going books have more narration and description, which results in longer, denser paragraphs. A paragraph’s main purpose, he states, is to deliver and explain a point, as effectively and economically as possible. This point should ideally service the plot or character development.

On the topic of backstory, King says that it is ‘back’ for good reason and doesn’t need to be told in absolute detail, but that it’s still important to make sure you’ve researched everything relevant, so you know how it plays into the plot and affects the characters. This largely includes details of a book’s setting and context. If you’re writing a war story you should know the relevant history and military procedures, or with a crime novel you need to be familiar with police and criminal practices. Genres like science fiction or fantasy on the other hand require you to invent a lot yourself. Whichever field you choose though, you’ve always got to do your homework.

King’s words about habit and routine have had a lot of influenced on my own writing practice. A good writing space is one where you feel comfy but not distracted. For me, public settings with too many strangers close by don’t suit. His advice has also affected my discipline too. King advises a daily target of 1000 words. I’m not quite as disciplined as him, but it’s certainly helped me to learn that consistency pays off, like building a muscle.

One particularly interesting comparison I discovered was how King tells of his inspiration for the book Misery. The premise of a crippled writer held captive by a psychotic and obsessive fan came to him in a dream while on a flight. Interestingly, both myself and friends of mine have also taken writing inspiration from dreams, with supernatural themes often popping up. Inspiration is plentiful in a ridiculous number of places if you just keep an eye out.

King also breaks down story with elegant simplicity. In essence, story is as simple as three things: narration, description, and dialogue. Plot is a lot less relevant than most people think and shouldn’t necessarily be a dictating factor. Plot development is fine so long as it’s surface level. What you want is for the characters to drive the plot rather than having it drive them. As someone who likes an outline, I wouldn’t say I entirely agree, though I’d still say that character autonomy should always take precedence. Still, an outline is something I often treat more as a guideline than a rule.

I was especially intrigued when King brought up the topic of theme. He says that theme isn’t as important as academic obsession suggests (as an arts graduate, I can definitely relate) but it should still maintain a presence. It’s something a writer should decide on after finishing their first draft and analysing it to see what most comes to mind and what their story is about. Theme ultimately boils down to the message your story’s sending and the underlying meaning of it all. The second draft is where you pick out the themes of importance and really turn them up. Prominent themes that King cites in his own books include: the Pandora’s box of technology, reconciling the possible existence of God with a world full of horror and suffering, the line between fantasy and reality, and the influence of violence on good people. “You undoubtedly have your own thoughts, interests and concerns, and they have arisen, as mine have, from your experiences and adventures as a human being,” King says. “You should use them in your work.” The only time when King says putting theme before story works is with things like allegories or satire, as making a point is usually what’s more important in these works. Generally though, theme is more often something you discover. Your story’s statements and messages will become more apparent to you as you tell it, allowing you to put more of the spotlight on them.

King’s words on revision and re-drafting also come in handy. He says that in your first draft you should simply get the story down. The second draft is about fixing, improving and making appropriate changes. In the third (which he doesn’t entirely consider an additional draft) you should polish and smooth out anything you may have missed, while still making any additional changes that come to mind. The example he provides of a small section of an unedited first draft followed by a second version showing and explaining all its changes is especially helpful. Re-drafting is simply going back and making sure your work does everything you need it to.

King also offers some particularly helpful tips about publishing, and for dealing with agents and publications. The example he provides of a cover letter and the explanation behind it are a valuable bonus for writer-readers. Presentation will get you a long way, he reminds us.

A mantra that King repeats throughout On Writing is “read a lot and write a lot”, something many writers say. King admits to being a slow reader, which I can also relate to. I often feel that it’s not something that comes naturally to me like with some people. I typically avoid reading too much at once as it strains my ability to remember and process it all. What I’ve come to learn from reading more and more though is that you only get better with practice. I’ve tried following King’s advice on the ease of reading and just how many places are suitable, bringing my book with me wherever I might have some spare time. Public transport is one good example, and it’s certainly a lot more rewarding than scrolling on my phone. As for his advice on writing a lot, it’s something I make a point of doing every day. Friend of mine who write tend to do so less often, but in bigger chunks, so our overall output tends to be pretty even. Again though, consistency is what’s important here.

King points out that it’s important to remember who your ‘Ideal Reader’ is. This is who you’re primarily writing for, and who’ll most likely be the first person/people to read your work. For him it’s his wife. King points out all the ways in which an Ideal Reader is of help. Usually, they’re on point about what’s good and what’s not, and their reactions are often very telling. I too know this to be true from experience. Your Ideal Reader/s are people that care about your work and whom you can trust. Helping you is in their best interest. You’ll always get an honest but well-intentioned response.

The most impactful part of King’s book is toward the end. Here he switches back to the autobiographical style to describe an incident that occurred while writing On Writing. While out walking during a family holiday he was severely injured when he was hit by a van. This section, detailing his brush with death and his torturous recovery puts a lot of his points into perspective. For King, writing was something that helped him immensely in the aftermath of his ordeal, a form of therapy you could say. He ends this story by using it to demonstrate the meaningfulness of writing, and how positive and enriching an effect it has, both for him in a dark time and also, potentially, for other writers. As King puts it: “Writing isn’t about making money, getting famous, getting dates, getting laid, or making friends. In the end, it’s about enriching the lives of those who will read your work, and enriching your own life, as well.”

The original version of this article was posted on ‘The Footy Almanac’ at: https://www.footyalmanac.com.au/almanac-book-review-stephen-kings-on-writing-reviewed-by-ben-kirkby/.